Back when I bought my first box of Warhammer 40,000 miniatures, I naïvely expected to open the box, follow the assembly instructions, and end up with a valid battle unit. What I found instead was that every soldier in the box could be assembled with any one of several weapons, heads (helmet and no helmet), and so on. But some parts are mutually exclusive, and some belong to specific components, and the game rules restrict how many of each option you can take. Sound complex? Think of it as something of an organizational challenge. Those little boxes of 10 miniatures here and there turned out to be good practise, because I recently purchased the huge Horus Heresy: Age of Darkness box set , and I was well prepared to assemble models with military precision.

If you're new to wargaming and haven't even purchased your first model kit yet, then you should read my posts on how to build an army for Warhammer 40,000 and how to build an army for wargames. Those posts explain the process of which kit to purchase.

1. Study the sprue (and instructions)

A trick I learned from "generic" model kits that often lack instructions at all, is to study the sprue before you do anything else. I don't mean glance at the sprue as you take it from the box. I mean sit down, turn on a lamp, put on reading glasses, and take a mental inventory of every part. You don't have to know what the part is, or how it fits together with another part, but you should have a general understanding of what parts you're going to be working with. Usually I count the bodies on each sprue, and then look to see how many arms and weapons and heads are also on that same sprue. Usually that gives me a pretty good idea of just how many different options I'm facing.

A "bad" habit I picked up from building Lego is to open a box and discover what pieces the box provides as I assemble the model. That works fine for Lego, because I always build exactly the model in the instructions first. I don't need to know what pieces I have, because I trust the instructions, and there aren't any options in instructions because you use every brick in the box. Don't do that for wargame model kits. Take an assessment of what you're working with first.

After have some idea of how many plastic parts you're going to have to stick together to get coherent models, look at the assembly instructions. Games Workshop invariably includes assembly instructions with Citadel models, but not all companies do. It's important to look at the build instructions because they make it clear when certain parts are incompatible. For example, in my Age of Darkness box, there are 5 different poses of space marine bodies, but only 1 pose is suitable for the parts that designate a sergeant. Had I started planning my build before I knew that, I might have used up the bodies for rank and file marines, leaving no body to be upgraded to sergeant.

2. Read the rules

Speaking of rank and file marines and their sergeant, the next step is to go back to your game's rules for a reminder on what makes a valid army unit. In Warhammer 40,000 and Horus Heresy, a unit is defined in part by a number of soldiers, and out of those soldiers usually 1 can be designated as the leader of the unit. In many games, there are restrictions on, or costs for, specific weapons, so you wouldn't want to build a unit where all the soldiers are carrying a rocket launcher each. Your army rules (or codexes, in Warhammer) inform you which of the many possible options contained in a model kit you can actually field.

3. Create a schema for your build

Finally, create a schema for your build. A "schema" is a repeatable template, and I create it based on the unit definition and not the sprue. I do this because a unit might have, for instance, 9 soldiers and 1 leader, but a sprue might only have 4 models on it. Focus on what the rules allow, and trust that the sprue provides for all options made available by the rules.

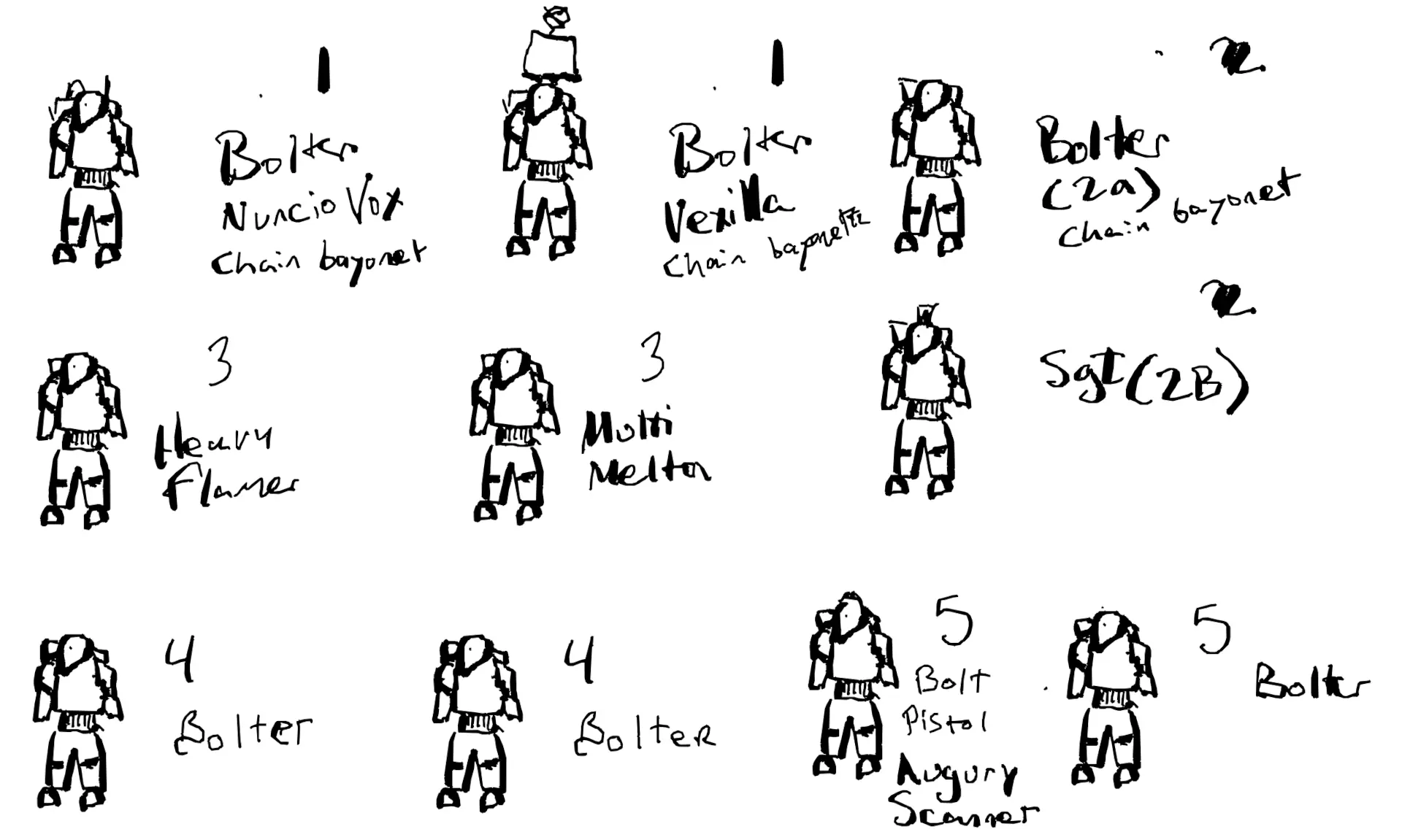

Personally, I sketch it out for myself on digital paper. Specifically, I list what each soldier in a standard unit needs to be built with, including pose, weapon, and any significant extra gear. By "significant" extra gear, I mean gear that costs extra points (like an augury scanner in Horus Heresy) or changes the soldier's role (like a sergeant's crest).

I don't add greeblies to my schema, because that's sort of my creative outlet as I build (for instance, I usually glue a grenade to at least 1 soldier if the unit is capable of throwing grenades, and maybe I'll add an extra pouch here or there just for added visual distinction).

Build an army

Armed with my schema, I sit down at my workbench and follow instructions. Following my schema, I build a complete unit and then start back at the beginning and build another one. Alternately, I build some number of soldiers to satisfy how many units I am building. Either way, I'm not building blindly. I know exactly how many of each soldier I need, and which components I need to ensure it has included on it.

There are so many possible army build-outs for wargames, which can be overwhelming. A common response to being overwhelmed is to just not do anything at all, and I wonder whether that's a leading cause of people amassing boxes of models that they never get round to assembling. I don't really have that problem. If I buy a model, I'm assembling it, painting it, and playing with it. But build options definitely were a cause for delays in my builds, and sometimes serious mistakes. There are absolutely some soldiers in my Genestealer Cults army that ended up with the "wrong" powerpack because I hadn't reviewed the instructions thoroughly before assembling, and ended up with leftover parts that didn't quite fit (I ended up grafting a third limb to fill a gap, and it's fine!) Now that I create a schema for my units, there's no delay (aside from workbench real estate) in getting round to building, and there are far fewer mistakes. Plus, you get to say "schema" and "schemata" as much as you want, and both of those words make you sound very serious and grown-up while playing with toys.