With the exception of a handful of pioneering academics and specialist publications, serious critical consideration of gaming as an art form feels, to me, to be seriously lacking. Sure, it's commonly accepted that gaming is now very much mainstream, but it's pretty clear that what most people are talking about when they say this is Call of Duty and Candy Crush. I'd argue that this is a terrible mistake. High end, complex games are material which should not - cannot - be sequestered generationally. Academics and reviewers who are rich in experience and expertise in other forms need to engage with this art form or face missing out on the richest and most complex thing to happen to creative expression since someone ran a reel of film through a projector. This is driven not least by the necessarily multi-disciplinary approach which must be applied to fully understand such works. There are few better arguments for this than the astonishing master work, The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt.

The sheer scope of the work is awe inspiring. In volume alone, the creative output dwarfs any contemporary work in any other medium, and there's the added consideration that all of this content has been crafted with loving care and attention to detail, and each element linked and interlinked in a decision/narrative tree of mind-boggling complexity. And as if that weren't enough, it's beautiful as well.

Yehezkel Kaufmann's conception of the meta-divine realm may not, on the surface, seem to have much to do with a sword-swinging, bodice-ripping computer game, but then that's not all there is to The Witcher - not by a long shot. Kaufmann's idea that the pagan universe contains a realm of being from which the gods themselves spring is important for many reasons, but here we're focussed on the way this affects ancient versus modern mentalities. In a culture dominated by transcendent monotheism, our understanding of ancient mentalities can be seriously hampered by the lingering formative effect of the big three. The idea that there is a place from which the gods come creates startlingly different interactions with the tangible universe. Depending on the nature of the relevant mythology, commonplaces like blood or water can become imbued with divine significance, and long-forgotten features of everyday life like sacred landscapes and ritual calendars suddenly make perfect sense. By transposing and synthesising many systems of meta-divinity into interactive dramatic and narrative form, The Witcher allows us to experience and understand these mentalities through a faithful and sensitive simulation of sacred liminality. Vaguely remembered and poorly understood superstitions are expanded and explained in a way which promotes understanding of the dim past in ways which history teachers can only dream about. It may seem unlikely, but anyone who has engaged with The Witcher is much better equipped to understand complex ideas like immanence and meta-divinity than someone who hasn't, simply because, on some level, these concepts have been lived and experienced.

The broad premise of the game centres on The Wild Hunt, a piece of European folklore having to do with the storm gods, elves, the departed, or the dread hound, Black Shook, depending on where in Europe the tale is encountered. The story goes that whenever there's a storm, it is The Wild Hunt galloping across the sky in pursuit of souls, and if Black Shook catches your eye, you are forever lost. So far, so simple. Layered in amongst this, however, is the idea of the protagonist/avatar, Geralt of Rivia, as a specially bred monster hunter called a Witcher. What this creates (besides complex explorations of the morality of professional warrior-hood) is a pretext for the compilation of a wonderfully comprehensive bestiary of practically every nightmare creature from Classical Greece to modern times, as well as somewhat more ambiguous or benign supernatural fauna. As an ethnographic achievement, The Witcher's bestiary dwarfs most examples from the mediaeval period, the time at which this literary form reached its peak, and for sheer preservation and detail of monstrous traditions, professional and amateur ethnographers and folklorists alike should find significant utility in the collection, in spite of its fantastical lack of context and attribution. It's not just about listing or preservation, though. The genius of the bestiary is in its detail and synthesis. The grand literary achievement of the monster lore in The Witcher is the deft manner in which an enormous, eclectic grab bag of superstition, folklore, and myth has been woven together into a coherent universe. The effect of this is to prompt new and interesting ways of thinking about humanity's fascination with the monstrous. The juxtaposition of disparate traditions highlights their similarities, and hints at the central truths of human conceptions of monsters, as well as exploring the essential dichotomy of beauty and horror. Common threads in logic, ritual, cult, and system catalyse and highlight ideas about transformation, therio and anthropomorphism, and humanity's intimate yet profoundly uneasy relationship with the natural world and the murky intersections of the conscious and unconscious.

The Witcher's literary merits do not merely rest, however, on mimesis, archaism, and preservation. The foregoing aspects, as substantial as they are, are merely peripheral elements of the narrative. The story itself is a grand interweaving of the public and personal, high drama and low comedy, intertextuality and resonance both comic and poignant, all heavily imbued with themes of justice, humanism, high statecraft and the idea that all decisions, however small, can have significant impacts. The element of active decision making present in gaming means that the thematic messaging has an immediacy and impact which far outstrips the capacity of any other form of literature. The player is not just an observer of the work's themes, but a responsible actor in their realisation. It is this element of responsibility which, in a well-crafted game, provides a far more intense experience of the core ideas of a story than is possible in print, image or film. The player is bowled along from decision to decision, the fates of individuals, communities, and nations in their hands. This isn't just about fantasy or role playing - the world of The Witcher is peopled with characters depicted such that the player invests emotionally in their existence, and the potent consequence of this is that the ideas and dillemmae unpacked within the story have vibrant and actual life. This constant load of moral responsibility forces players to consider fundamental questions of good and evil, and to interrogate their own moral choices, the basis and validity of their ethical positions and comfortable assumptions - the exact same questioning which is provided, at a considerably less confronting distance, by the philosophical bases of tragedy.

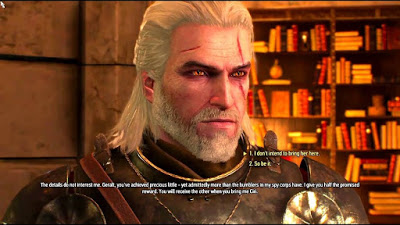

I often encounter a weird bias, when it comes to the visual product of games, reminiscent of the old prejudice against comic books and graphic novels. These latter are, of course, firmly entrenched in the mainstream now, along with the quotidian obviousness of Banksy, and the near meaningless jingoism of other forms of pop art. And yet the magnificent beauty of so much of gaming's visual art gets little to no serious attention. Whether it be hyper-realistic cinematic trailers like the one above, or the dauntingly global pool of art and art styles subject to mimesis, pastiche, elaboration, or straight use, The Witcher is a staggering compendium of artistic achievement.

The landscape itself is moulded with fine aesthetic (though definitely not geographical) logic. Dead ground, terrain, and cover are not just used tactically in The Witcher, but are also exploited to provide countless openings of sudden and breathtaking vistas. The construction is as intricate and deliberate as any Classical garden or Romantic grotto, and at least as powerfully and consistently sublime. The two key differences, however, are in the fact that the world of The Witcher is not a single garden, but a series of fully realised and populated simulated worlds, and that this is a landscape which is not limited to vicarious or imaginative experience, at least visually. It is also, to a certain extent, performative, in that the aesthetic reality of each environment is predictive and productive of the nature of its events and populations. This performativity is not just unidirectional either - the player's actions will form and shape sections of the world, providing dramatic and immediate visual manifestations of moral and sociological impact.

Beauty, male and female, pristine and grotesque, is a significant part of The Witcher's visual world. Echoes of Rococo and Pre-Raphaelite starry-eyed eroticism abound in the depiction of practically every character, be they young, old, halt, hale, pristine, or disfigured. There is also the uncomfortable Geigerian sexualisation of the grotesque and horrific. Monsters are lovingly rendered with exaggerations of tongue, breast, thigh, and curve, which make a further complex comment on the essential nature of monsterism - the inflation, subversion, or inversion of decidedly human characteristics which separates the monstrous from the merely frightening. Visually as well as textually, The Witcher points again and again to the concept of our darkest evils deriving their genesis and expression from deep within our image and awareness of ourselves.

At this point, this author's dilletantism in the field of visual art brings about a frustrating halt. While quite a lot of the game is recognisable as run of the mill fantasy art, there seem to be frequent excursions into much higher realms of visual expression. Someone much better qualified should devote some attention to this work -- attention which it richly deserves.

The sheer plethoric volume of material in The Witcher is such that I haven't even touched on music, higher ethics, or the detailed exploration of human relationships abundantly present in the game. Questions about the value and absolute integrity of sovereignty, the dichotomous relationship of freedom and civilisation, historical simulation and representation, and much much more are all contained within this sprawling framework. And it's not just The Witcher, though it's a prime example. Whether the player is deciding the overall policy of intergalactic colonies in Mass Effect, conducting complex, multi-handed truce negotiations in Skyrim, or weighing the competing philosophies of transhumanism, reactionism, and liberalism in Fallout, the medium of gaming can provide a depth and level of narrative and thematic engagement unrivalled in immersion, impact, and sophistication in any other existing form. Creators, critics, and academics ignore this world at their peril, and to their significant loss.

Image: All images are property of CD Projekt Red, and are released for media and promotional use. Header image modified for size by David in Inkscape.