Right off the bat, it's important to understand that every GM is different. No two styles of running a game match completely, nor should they. And while there is no one correct way to run a game, there are plenty of ways to do it poorly. The GM wears many hats, but in my opinion, the most important duty is to make sure that everyone has a good time. Your players are giving you an evening out of their lives. Next week they'll probably give you another. It's your job to make sure that time isn't wasted.

By definition, games, even role-playing games, are a form of entertainment -- like reading a book, watching a movie, or enjoying the circus. When you go to that, the GM is the ringmaster, presenting the show; while the players are both the audience, and the main attraction. The GM controls the world, the people, the monsters, the history, even the weather. The GM controls everything, in fact...except for the player characters. A game master presents the situation, but it's the players who decide what to do with that information.

Now, this is all pretty vague, and describing RPGs is far less informative than playing them. If you are in doubt about how this type of gaming works, I encourage you to go and listen to Hacker Public Radio, episodes hpr2424, hpr2429, hpr2437, hpr2444, hpr2455, Klaatu's five-part cyberpunk adventure, Interface Zero (a.k.a., Job inSecurity). These are excellent examples of actual game play. Even if you're already familiar with how RPGs are presented and experienced, you'll appreciate those shows.

Now then, almost all games are divided into genre types: sword & sorcery; space opera; spies; super-heroes; and pretty much everything else. And I mean everything! If there's a genre of fiction and storytelling that you enjoy, chances are there's a game or game setting for it somewhere. The most popular style of RPGs out there are fantasy. Think Lord of the Rings. Think Harry Potter. Think of anything, in fact, because all of it is possible.

A staple of high fantasy gaming is the dungeon. That term has two meanings in this sort of game: first, the usual definition of what essentially amounts to the basement of a castle, complete with jails, interrogation rooms, storage rooms, and more. The other meaning refers specifically to a type of adventuring environment. Both of these are usually found underground, but an adventuring dungeon may have nothing to do with any castle. It might be a lost crypt, a cave system, an abandoned gold mine, or the lair of some horrid beast that's been terrorizing the countryside. In the dungeon might be enemies, monsters, and treasure protected by deadly traps. Magic abounds. There might be puzzles, dark secrets, or a kidnapped prince to rescue.

As a new GM, you can start off in any manner you like, but a great way to get used to how the game works, and how the whole process of providing an evening's entertainment to your friends or family works in this context, is to create a dungeon from scratch, and run your players through it. This article assumes you own copies of any relevant rulebooks for the game. It's kind of hard to play without them!

Dungeons generally require set-up time; that is to say, you have to design it in advance. Klaatu and I are currently working on ways to ease that burden, with the ultimate goal of eliminating the pre-work entirely. For now, let's talk about the traditional way to approach all this. What follows is a step-by-step process, but understand, it's only one of an infinite possible number of them.

STEP 01 -- CREATE THE COUNTRYSIDE

Some GMs say creating the world is the first step. Some say creating the godly pantheons for that world is the first. Some say it's the history, or the fantasy races. They're not wrong, but trust me, when you're just starting out, none of that stuff matters. In this example, you'll be running the players through a dungeon. That dungeon is out in the country, within the middle of a large forest.

It will make the beginning and end of the adventure easier if you have a small village nearby where the player characters all live. We'll call it Forestdale for the lack of anything better. In Forestdale, there's an inn or tavern. This is where people get together, tell tall tales, and become inspired to go adventuring. Let's give it a name as well: The Prancing Unicorn. That's home base. Every player character knows this place, and everyone in it knows them.

One of the stories being swapped at The Unicorn lately is about a tribe of dangerous creatures living in an underground lair somewhere within the forest. They are led by an evil wizard, or so the tales go. They have been attacking farmers and merchants who travel through the roads and foot paths of the woods heading to Forestdale to sell their goods. One of the merchants says he saw them escape down the Western path near the Old Bridge. The player characters all know where that is. Something must be done, but who would be brave or foolhardy enough to even try?

That's all the detail you need for your world right now. Remember, this stuff is new; no one wants huge amounts of detail just yet, least of all you. You'll have enough to juggle before the adventure is over.

STEP 02 -- CREATE THE DUNGEON FLOOR PLAN

One of the rumors to be heard at The Prancing Unicorn is that there's an underground cave system or labyrinth somewhere in the forest. Some say it's a myth, others say that their cousin's uncle's sister's best friend came across it once. Either way, its existence is shrouded in mystery, and people are said to go in, but not always come out.

This is your first dungeon. Believe me when I say you don't want to do more work than you need to. Let's make this dungeon a single level. Later on, you can add a secret panel somewhere that reveals a set of stairs down to a second level (and from there, a third, fourth, tenth, or more). For now, it's one level, hidden below the forest. It's dark, it's dangerous. It's plenty.

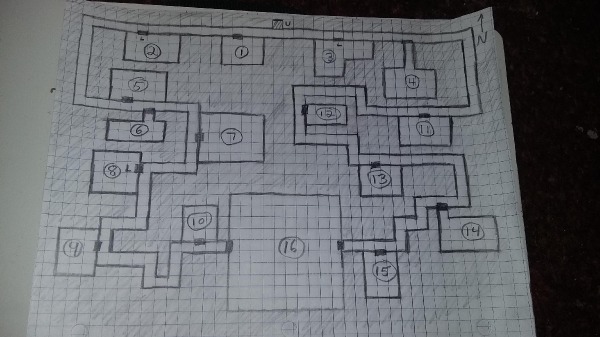

Putting a dungeon together can be difficult, but it doesn't have to be. The traditional way to create one of these is to use graph or hex paper and draw out the floor map. Each square of the graph paper is equal to ten feet (or, say, three meters). You make note of all rooms, caves, doors, hallways, stairs up and down, floor traps, hidden doors, and anything else you want in there. Be sure to put a set of stone stairs that lead from the forest above, down to this dank and gloomy dungeon. The mouth of this staircase is hidden behind some bushes. Looking carefully, the player characters will see many foot prints, coming and going.

There are no standard symbols for the different things on the map, despite what anyone might tell you, so for now, let's turn the paper landscape style, and holding it that way, at the top of the page outline one square of the graph paper with a pencil. Inside the square, draw three or four small lines at an angle. This will represent a set of stairs. Next to the stairs, write the letter "U". This is the way to get to the forest above. Granted, it's how the player characters will come down here to begin with, but once they are here, they have to go up to leave, hence the "U". If that's confusing, you can write, "To The Forest Above", next to this square, maybe with a little arrow. Either way, this is how the player characters will get in and out of your dungeon.

We're going to draw the floor plan from the top of the page down. The entire dungeon map will be on this one side of the paper. In the corner, draw an arrow pointing up, and put a letter "N" there. That's North. We'll be using compass directions from now on. Granted, when underground, it's hard to get your bearings without a compass, but for this first dungeon, we won't worry about that. North, South, East, West. It makes life easy.

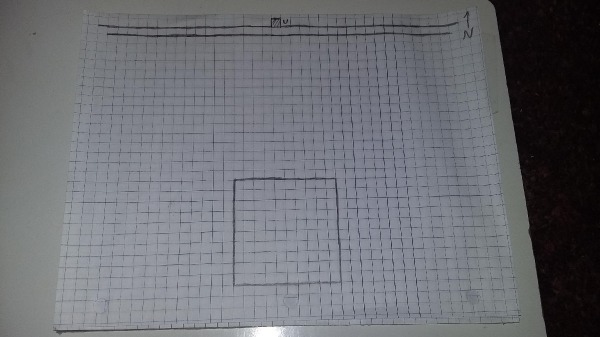

Near the bottom of the page (South), draw a box right in the middle that's ten by ten squares in size. This is where the dungeon tunnels all will be leading, and where we'll have the biggest fight of the adventure. We're setting that up now, so we always know where we need to go when laying out tunnels and other rooms. Now go back to the stairs at the top of the page.

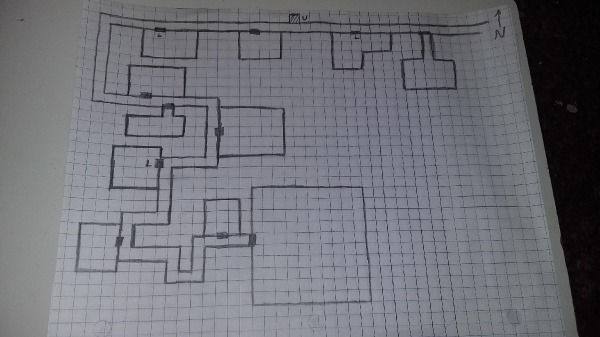

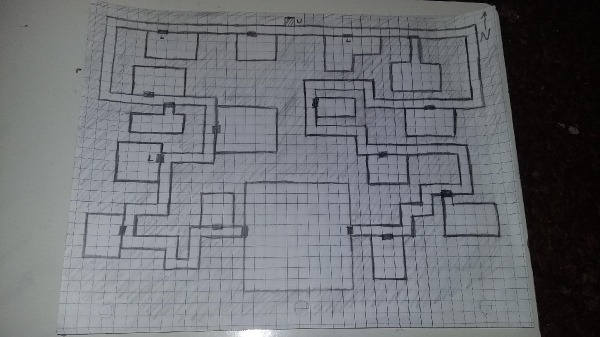

Draw a long line from the lower edge of the stairs going West. Stop the line a square or two from the edge of the paper. Now do the same thing going East. Next, move down one square, and draw another line parallel to both of these, going entirely from one side of the page to the other, East to West. You've just created a place for the players to explore, so imagine it for a moment: they come down some broken, forgotten stairs. Let's say they travel at least a hundred feet down, tripping over tree roots and walking through cobwebs, until the stairs deposit them in the middle of a dark tunnel, ten feet wide. It stretches to either side, running East and West out of sight (you know that it goes hundreds of feet in both directions, but you'll let them discover that for themselves). They listen, and can hear nothing but the scurrying of unseen vermin. At least, they hope that's what it is. Not a bad start.

Along this hallway, you'll draw little rectangles, like black bars, on random squares upon the Southern side of the tunnel. Not too many, just a few here and there, with generous space in between. These are heavy wooden doors. Some may be locked, some not. That's your choice. If they are, put a little symbol near them. It could be as simple as the letter "L", so let's go with that. Now you know where the all doors are in this particular tunnel, and you know which of them will be a challenge for the player characters to open.

This is just the first tunnel of a larger complex. This complex can be as big or as small as you'd like. Let's say it's moderately sized. Before we draw branching hallways, let's draw the rooms behind those doors. This will tell us how much map space we'll have for further tunnels. Some GM's like to draw all the tunnels first, and then fit in the rooms. You can do it however way you want later on; right now, let's just use this method. Pick a door. Draw a box behind it, three or four squares in size. That's the room. Do the same behind the other doors. Make the rooms different shapes and sizes, but not too big. Let the big room at the bottom be the star. When you're done, you have a huge tunnel, with several mysterious doors, behind which are some good-sized rooms.

On the part of the tunnel that ends on the West side, draw a connecting tunnel South for eight squares, and then turn the direction back to the East. Draw this tunnel going that way for ten squares. Put a door or two along here, and draw some rooms for them. Turn the tunnel South again, and go five or six squares, and turn it East again for four squares. Draw a door and room. Maybe it's locked, maybe not. Continue with this meandering, jagged floor plan, wandering East and then West, but always moving South. Add occasional doors and rooms as you go, until your tunnel finally ends on the Western side of the large ten-by-ten square room at the bottom of the page. Draw a door to get in there.

Now go back up to the long tunnel at the top, and repeat this whole process on the Eastern side, eventually bringing that part of the tunnel to the Eastern edge of the big room at the bottom. Put a door there.

At this point, number your rooms on the map, starting at the top and working your way down, until you've marked each one. Room numbers are essential, because you'll be keeping track of each one.

The floor plan to your first dungeon is complete. Now you need to put interesting things in it.

STEP 03 -- POPULATE YOUR DUNGEON

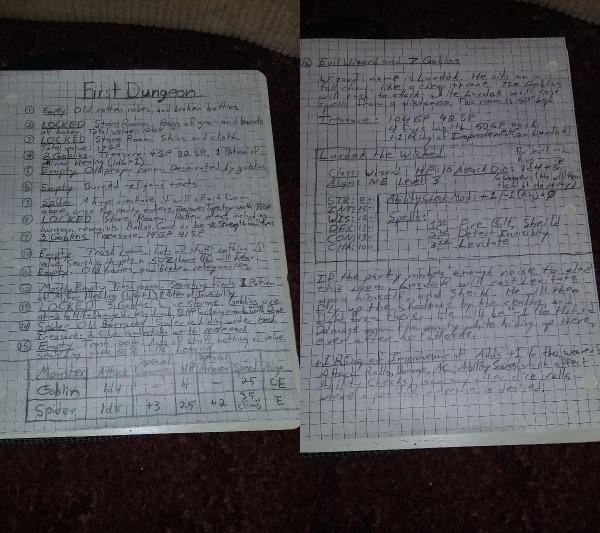

Okay, on a separate piece of paper, list the rooms of your dungeon. Start at #1, and go down. Beside the room number, write a brief description, along with any monsters, treasure, or other points of interest. You'll be consulting this list throughout the game, so write down everything you need to know in order to minimize the amount of time that you'll inevitably have your nose in the rulebook during the game. Monster statistics, including their weapons and the damage that they do, should all be on this list, though there are ways to simplify the process, one of which I'll go into.

When putting creatures and other items into your dungeon, the first thing to remember is not to overload it. Not all rooms need monsters or treasure. It might be helpful to think in terms of what you'd like to see in the dungeon as a whole. Remember the stories of evil creatures, and possibly a wizard, which you heard at The Dancing Unicorn? We'll use that as our springboard. This is a first dungeon, not just for you, but also for the player characters. Starting dungeons mean low-level monsters, so let's go with goblins, which are short, mean creatures with a penchant for violence and mayhem.

Goblins are generally quite impressed with magic, so we'll assume a wizard of dubious character has bullied a small tribe of them into being his thugs. They've been waylaying passing merchants and farmers, stealing their wares, and carrying off food (along with the occasional peasant worker, as goblins love the taste of human flesh). Stupid, but dreadful creatures, they have displayed a level of tactical organization that's not normal for them. This, of course, is because the wizard is in charge. Look up the statistics for goblins in your rulebook, and learn what they're like. For this adventure, we're not going to worry about goblin captains, or goblin chiefs, both of which are tougher than your average goblin. No, all the creatures for this adventure have the same statistics. Don't drive yourself crazy writing these stats down, over and over. Write them once, at the bottom of the room list page, and every time the player characters run into goblins, consult those stats right there, instead of juggling the rulebook.

Let's say there are a total of fifteen goblins in this dungeon. They won't all be in one place; the player characters will encounter a few of them here and there, in various rooms, or maybe just wandering the tunnels. The rooms themselves will have the spoils of all their raids, including barrels of wine, hams and sides of beef; furs, and a few copper, silver, and gold coins. If there's wine in one of the rooms, maybe the goblins there are drunk, fighting at a penalty to hit and damage. And once again: not all rooms need to have monsters or valuable things in them. Maybe this was once a temple, and there is just broken furniture and rotting religious robes in some of the rooms. In one, there might also be a tapestry against the wall, depicting a miracle of whatever god this place was once dedicated to. What you might not tell the player characters up front is that this tapestry could fetch a fair amount of gold coins in the market back in Forestdale. Too big to carry while exploring the dungeon, such a thing could always be rolled up and fetched on their way out. Not all treasure is found in wooden chests.

Then again, a lot of it is, so why not put one in the big room to the South? Of course, you have to defeat the evil wizard and his goblin cohorts first, who are hanging out in there. As a rule of thumb, you might want to sprinkle half the goblins throughout the dungeon, leaving the other half here, for the final fight. Stealth matters. Approaching the big room noisily and kicking open one of the doors is not stealthy. The player characters might be able to catch the wizard and his minions off-guard, if they move quietly. You may (or may not) want to suggest that.

In order to be a credible threat to the player characters, this wizard should be of a slightly higher level, say 2nd or 3rd. He'll have some aggressive spells, and he'll have his goblins handy. You'll roll up the wizard the same way the players rolled up their characters, only you'll make him more experienced, and with more spells at his command. Maybe he even has a magic item of some sort. Should the players defeat this guy, the magic item will be part of the treasure; until then, it's something the wizard will use against them, if at all possible. Don't make it too tough. Maybe don't make it tough at all: a +1 Ring of Protection, maybe. Or perhaps, a +1 dagger. That might not sound like much, but it's more than the player characters will have just yet.

Not enough excitement, maybe? Just add in a couple of giant rats in one of the rooms. Maybe some large spiders in another. Don't forget to put their statistics down in the description for their rooms. Judging how tough or easy a dungeon needs to be comes with experience. My suggestion is to err on the side of toughness, and put more challenges in there than maybe you feel comfortable with. If the player characters are looking depleted and injured, you can easly just tell them the next room they come to is empty (instead of being filled with snakes, like you'd planned). Also, it doesn't hurt at all to remind the players now and then that it's okay to retreat. They can always come back another day when they've rested and made plans to defeat the wizard and his goblin hoard, based on the knowledge gained in the first adventure. It sets up a grudge match...the heroes vs. the villains that are threatening their town. You, as the GM, can just repopulate any killed goblins, and move them around a bit in the dungeon so they're not in the same rooms as before (though the big room to the South should still be reserved for the final fight). This represents two night's worth of entertainment for the effort of only one.

And there you have it: a stocked dungeon that dovetails into the local lore of the countryside, ready for your players to explore.

Tunnel below Hampoort Grave by Vincent de Groot Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Modified by David in Inkscape.