I've read my fair share of player handbooks and rulebooks, and lots of game mastery guides, and yet I still have a nagging feeling that nobody has yet provided a straight-forward, no-nonsense "recipe" for the mechanics of running an RPG session. Most books assume that if you're ready to take on the role of a Dungeon Master™ or a game master, then you must have played an RPG before and therefore understand what the GM does. That's a pretty fair assumption. You can find online videos of truly talented game masters, like Chris Perkins, Matt Mercer, or Troy Lavallee, demonstrating exactly how a game can be run. Then again, that's a lot of information to take in, and it assumes a certain degree of performance. That's not for everyone, and it's certainly not how kids playing AD&D back in the 80s and 90s figured it out. So I looked back at years of playing through pen-and-paper dungeons, and assembled this concise and pragmatic guide on how to run an RPG.

I don't assume you have ever played an RPG, but I do assume that you have purchased an RPG rulebook and have access to friends who are ready and willing to play. If you haven't gotten that far yet, please do read my getting started article.

The short version

It's pretty simple, in theory:

-

Tell the players where they are and what they see around them.

-

Listen to the players when they tell you what they want to do.

-

Tell the players the outcome, based on your privileged knowledge of the game world or on a roll of the dice, of their actions.

This is a loop, so just cycle through these steps until the players achieve the stated goal of the game.

You're a GM!

The long version

So you want to play as the Game Master? I, like many game masters, have run games that have involved lots of prep work, and I've run other games that involved no prep work at all and were based entirely on random tables and a quick wit. But you have to start somewhere, so here's what I think is a sane process for easing into game mastering.

Generally, it starts with some amount of prep work.

Preparation

- Find an adventure to run. This is the scenario you and your players will experience when you sit down at the table to play. It's arguably the game (the rulebooks are the game mechanics). Wizards of the Coast, Paizo, Catalyst, Kobold Press, Frog God, and many others publish officially-sanctioned adventures (sometimes called "modules" or "adventure paths") written by professional game designers. Published adventures provide the story framework for your game.

Not all systems publish adventures, though, or you may choose not to use one. If that's the case, spend some time developing a story. Writing a good game is part science, part craft, and part magic, but if you and your players are up to the challenge then running blindly through a story that's mostly being created spontaneously on the spot can be a lot of fun. If that sounds overwhelming, though, get a published adventure!

Quick tip: Free, small, or introductory adventures are often available from http://drivethrurpg.com, http://dmsguild.com, and https://www.opengamingstore.com

- Getting a published adventure is one thing, but now you need to read it. You don't have to read every word of it, but you should look it over. Don't put it down until you understand what the quest is, what the obstacles are, who the villains are, and what the primary settings are. Some GMs prefer to read over an adventure well in advance and mull it over in their mind over the course of a week, while others prefer to read it the night before playing so it stays fresh in their mind. You know your own comprehension style, so do whatever works best for you.

You might also sketch out a rough flowchart of how story elements connect, or jot down notes for yourself, or create an outline. Do whatever you think will help you keep the story of the game straight on game night.

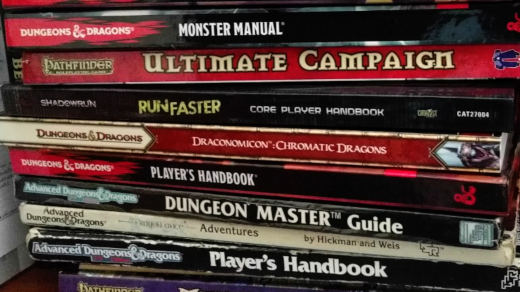

- Bring pen and paper, your rulebooks, monster manual or bestiary, and the adventure itself to game night. You may also want to bring the Dungeon Master's Guide or a book of game mastering utilities (random tables, traps, NPCs, and so on) to help you come up with fresh content when your players surprise you by taking a right at the fork in the road when you expected them to take a left.

You also need a set of die and, for the convenience of your players, some blank character sheets.

Playing the game

You're ready to play, so now what?

- At the beginning of a game, it's nice to let your players provide a quick overview of their characters. This helps your players understand who and what they're playing, and it may help you develop interesting story ideas to add to the game.

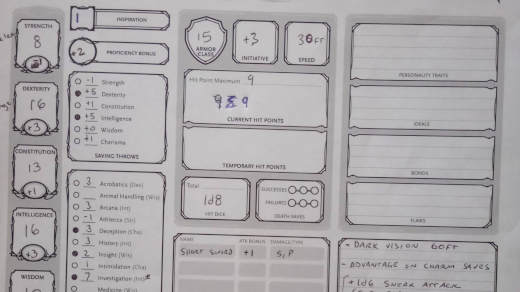

If your game spans more than just one session, then you might instead review what's happened in the story so far. This helps you and your players stay on track. If the players have recently leveled up, you can also review updates to their character sheets as a way of reminding the players of any new abilities or gear they can now access.

- As the game master, it's your job to keep your players aware of their surroundings. Sometimes an adventure tells you very clearly what to read to your players. Generally, a published adventure tells you what the players are facing, and it's up to you to convey bits and pieces of this information to your players, depending on what they ask. The rule of thumb is to start broad, and let the players guide you to specifics through questions and prompts, because if you try to narrate literally everything in a setting, it would take hours. Start broad ("You've walked to a small town square. There are three stocks in the center, and buildings that look abandoned, almost haunted, all around.") and then let the players engage.

- In video game or movie terminology, players generally control the "camera" once the location has been set. Let your players ask questions or take actions ("I look at the stocks"), and answer them as you see fit ("The neck and arm holes in the stocks have blood stains. They're closed and locked.")

The strength of pen-and-paper role-playing gaming is that the virtual world has, literally, infinite capacity. Video games and books must commit something to paper or code, but your virtual world exists only in your mind and can adapt instantly to whatever the players do. For instance, if a player decides to knock on the doors of all 15 houses in a cul-de-sac but you had only planned on them visiting 1, you have the ability to invent 14 more stories for each extra house visited.

No published adventure can possibly contain the infinite details you need for full player freedom. No matter how many times you GM, coming up with new story hooks and set dressing and non-player characters in the time it takes a player to say "I knock on the door" is hard! And that's exactly why indie game developers like Mixed Signals provide tables and lists of NPCs, traps, treasures, and a dozen other resources for you to refer to when someone asks you for an unexpected detail that neither you or the adventure authors could have possibly known to prepare in advance.

Most importantly, know that there's no rule in any RPG that demands the game master must have instant responses. If you have to take a minute to look through your notes or GM toolkit to find the contents of a treasure chest or to find an NPC table or look up a monster, then take a minute to do that. Don't apologize, and don't feel pressured or rushed; ask your players to wait, and then find what you need. Alternately, ask a player to find what you need; it's not a crime to pass a monster manual or an NPC table to a player so they can find the page you need, while you continue the narration for everyone else. Players know that you're not making everything up on your own, so you're not destroying any illusions, and by bringing everyone at the table into administration of the game, you're hopefully empowering others to game master later, and you're reinforcing the fact that game masters and players are more alike than they are different.

- Exploration of the world (the cycle of you telling players where they are, and then answering their questions about their surroundings) is a huge part of any RPG, but sometimes something particularly challenging happens. Your game rulebook and game master guide tell you when and how to manage these moments.

There's some flexibility here. Strictly speaking, any action that falls into a category of a skill on a character sheet requires a die roll. Then again, terms like Acrobatics, Performance, Persuasion, and so on, can seem pretty broad.

First of all, players often intuitively know when to roll die. It's the way the human brain works; a player knows their character's skills, so sometimes the actions they choose to take are chosen because it falls within a category of a skill they happen to have. A thief probably wouldn't ever think to look for hidden door if the thief weren't a thief, but a fighter (who would more likely think to pound on the wall rather than to slyly look for a hidden door). So if your player reaches for dice, let them roll because they're probably right.

Die rolls represent the chance of success or failure when a specific action is taken, but if you think hard enough about anything in the world you can find a chance of success or failure. As a GM, it's usually up to you to decide what's "important" enough for a roll. If a player tries to open an unlocked door into an abandoned barn that has no relevance to the story, then a roll is probably not worth anyone's time (although it's also a great opportunity to trick the players into thinking the barn could have been important by letting them roll to open the door, then rolling your own die as if letting fate decide whether a monster or some treasure was in the barn, and then telling them that the barn is empty).

In other words, it's part of the art of being a game master to determine when dice need to be rolled. Be attentive to your player's, and you'll get a feel for whether you're having them roll too little or too much. Worst case scenario is that die are only picked up for fights and a literal interpretation of skills: it works because those are the rules as written.

- As players accomplish tasks that have experience points (XP) associated with them, you should award your players with the XP they've earned. The adventure you're playing tells you what tasks are worth how much XP, and your rulebook tells you how much XP results in a new level.

Most game masters wait until the end of an adventure to tell players to level up, and some wait until the end of the adventure to tally up earned XP. It's up to you how you want to handle the administrivia of XP, but you should at least make note of XP earned as you play.

End game

Some adventures take 4 hours to play, and others take a year. It's down to the length of the written adventure and player focus. Either way, after the end goal has been reached and the adventure is over, there's a little bit of administrative work to be done. You should do this even if an adventure was "just" a one-shot; it's very common for players to come back for another game with the same character, so it's important to correctly track progress no matter how casual the game.

- If you didn't award the players with experience points during the game, tally up the XP and have your players add it to their character sheet at the end of the game. If they've leveled up as a result, they can refer to the rulebook for details on how to level up their character.

- Tell the players to refer to the rulebook for downtime activities. These are almost always beneficial to players: some get a job, others go on adventures "off screen", others learn new skills. Of course the player doesn't actually have to go home and play out the downtime activity, but if they read about their options and then come back next time able to tell you what their character did between games, then you can reward them with gold or a new skill or whatever it is that the downtime activity earned them.

Quick tip: The Ultimate Campaign guide from Paizo contains extensive rules for downtime.

- Jotting down some notes about the game session, or at least which adventure you played, is invaluable. Do this even if your players swear to you that they'll never be back to play again, because players surprise themselves and become addicted to RPGs. They may well come back, so you may as well have notes about important NPCs, significant world events, and which exciting adventure has already been done.

Live it

Pen-and-paper role playing games are fun in part because they don't start and end at the game table. You can build characters who may or may not ever go on an adventure, you can maintain a character's downtime between sessions, you can read up on lore, tour different villages and read the gazeteers of towns, collect tables and lists of forgotten spells, hidden treasures, and mundane citizens, and voyage to different planes and different worlds, all without sitting down at a table to play an RPG. In fact, you could almost argue that playing through adventures is the smallest part of a good RPG.

So don't constrain your time as a game master to the few hours a week you're sitting around with friends playing through an adventure. Make it a daily activity. Be a serious gamer, and you'll make a great game master.

Wizard girl and interdimensional tablet images by Zonked Creative Commons cc0.

All others by by Mixed Signals. Creative Commons BY-SA.